Stories of War

World War I

1917–1918

When the United States joined World War I in 1917, Black Americans were still denied full participation in American society. Yet as civil rights leader W.E.B. Du Bois declared, “First your country, then your rights.”

The 367th Regiment Infantry, the “Buffaloes,” presented with colors, singing the National Anthem in front of the Union League Club, New York City.

National Archives

More than 350,000 Black Americans served overseas in the American Expeditionary Force. Like many times before, white leaders denied Black troops an opportunity to fight. The majority worked as laborers, clerks, and in construction and transportation. The all-black 92nd and 93rd Infantry Divisions were an exception. The 92nd served in the Meuse-Argonne offensive (September 1917-November 1918), and the 93rd was uniquely “lent” to French commanders. Between 40,000 and 50,000 Black American troops served in combat.

In November 1918, the 367th, a regiment in the 92nd Division, fought near Villers-sous-Preny, an area that had been heavily shelled with chemical weapons. Lieutenant E. B. Williams breathed in the poison gas used in the attack, but “maintained his post until all shellholes were properly covered and his entire area free from gas.” The commander of the 92nd commended Williams by name for his “excellent work and meritorious conduct.”

The 369th Infantry, known as the Harlem Hellfighters, spent 191 days in the front-line trenches—more than any other American unit. During that time, no men were captured, nor any ground taken.

“Big Nims” of the 3rd Battalion, 366th Infantry, who found great amusement in contemplating the grotesque appearance of his comrade with a gas mask adjusted over his face and head.

U.S. Signal Corps

Harlem Hell Fighters in Séchault, France on September 29, 1918 during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

U.S. Army

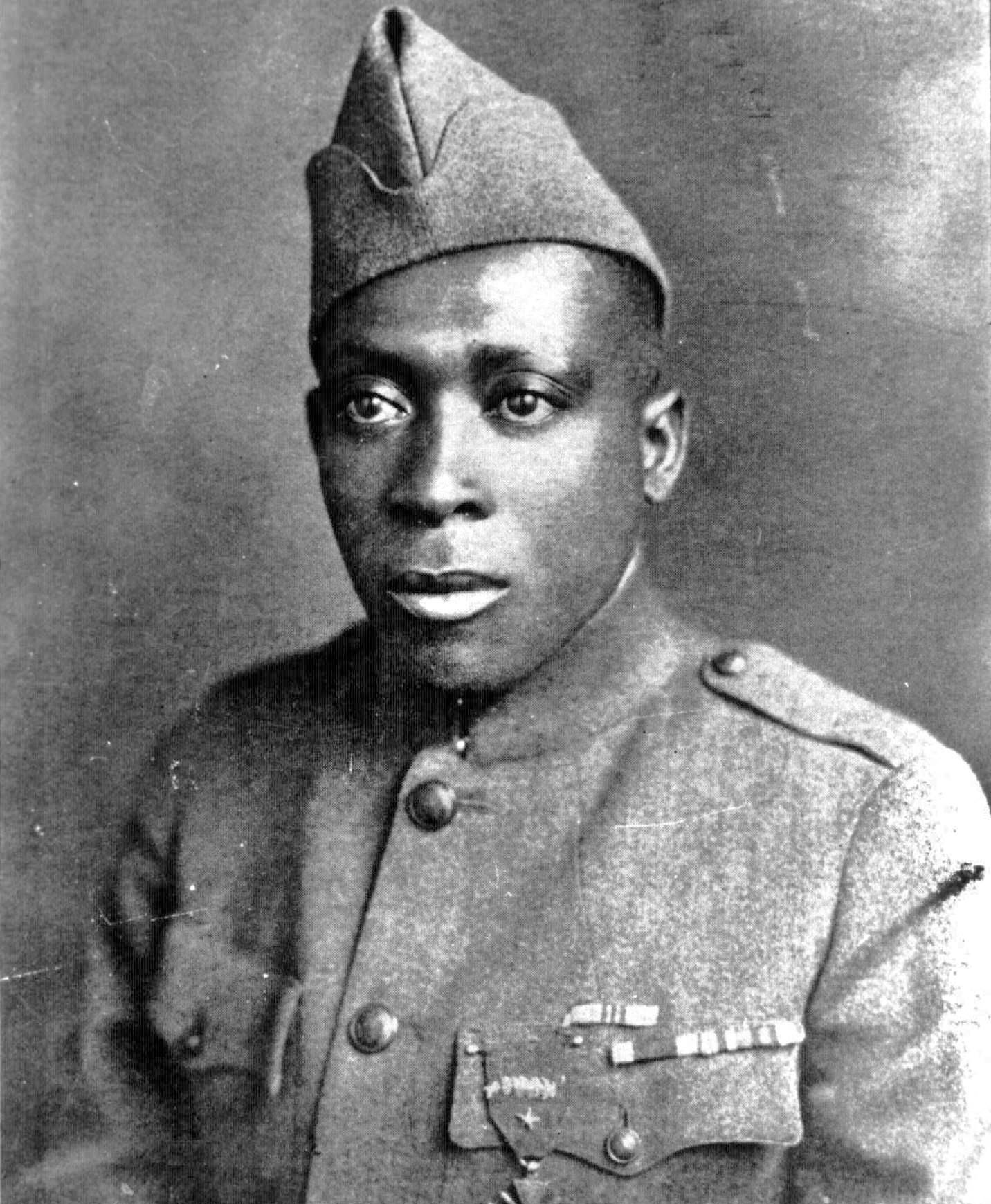

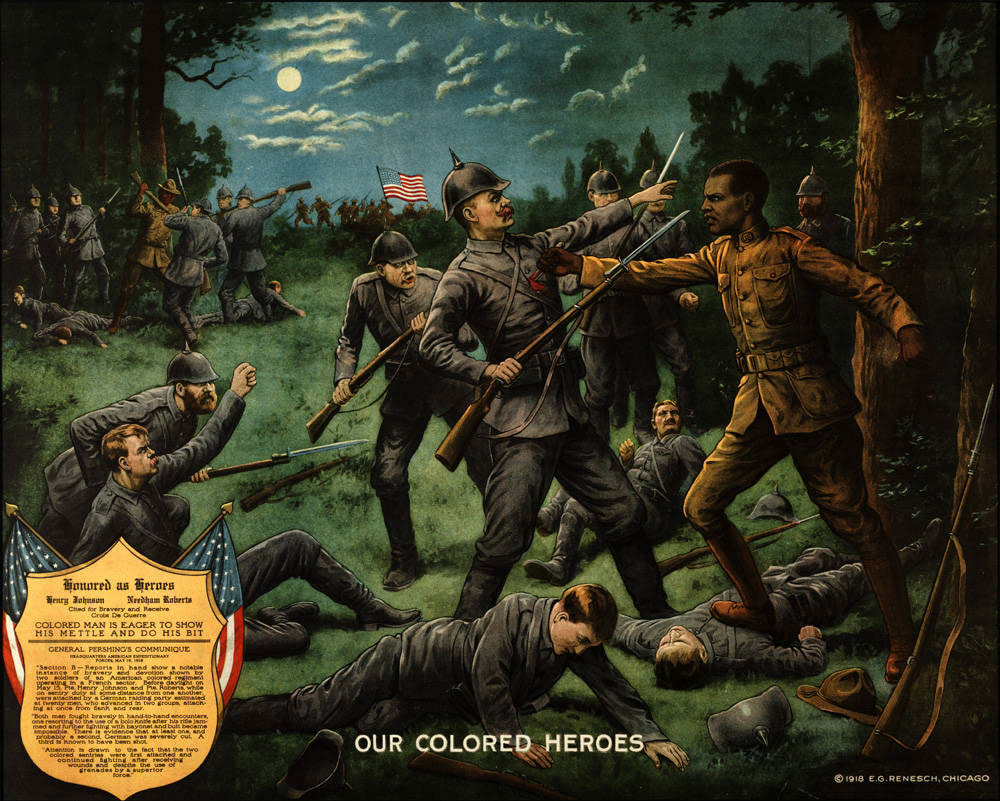

Two of the Harlem Hellfighters lived up to that name individually. On guard duty in June 1918, Henry Johnson and Needham Roberts fought off a 24-man German patrol. After Roberts was wounded too badly to continue, Johnson single-handedly killed several German attackers and suffered more than a dozen wounds in the process. He was awarded the Croix de Guerre—France’s highest military honor—for what became known as “the battle of Henry Johnson.”

Corporal Freddie Stowers, drafted into the 371st Infantry in 1917, found himself in a death-defying situation in the Ardennes in September 1918. His platoon was caught between German machine gunners, all the other officers killed, when Stowers took charge, crawled toward the enemy, and encouraged his comrades to follow. The men silenced the machine gunners in one trench, but Stowers led them toward a second. Wounded twice, he urged his men to continue, and they drove the enemy from the field. Stowers, age 21, died there. He was recommended for the Medal of Honor, but the application was “misplaced.” After the Army conducted a review years later, Stowers’s surviving sisters received his posthumous medal in 1991.

Troops of the Harlem Hellfighters, 369th Infantry Regiment, World War I.

National Archives

World War I was one of the first conflicts in which women could serve in official auxiliary roles to the U.S. military. Nineteen Black nurses assigned to the Army Nurse Corps served at Camp Sherman, Ohio and Camp Grant, Illinois, in 1918. More than 1,800 experienced Black nurses were certified by the Red Cross to serve with the Nurse Corps, but only a handful did: they were called into service only toward the end of the war.

The U.S. government officially allowed only three Black women to travel to France during the war. Addie W. Hunton, Kathryn M. Johnson, and Helen Curtis ran YMCA canteens and leave stations where African American troops could find reading material, refreshment, and rest Hunton and Johnson later wrote a book about their experience, which they called “the greatest opportunity for service that we have ever known.”

African American U.S. Army nurses at Camp Sherman, 1919.

David Graham Du Bois Trust, and the Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst

African American Gold Star mothers wave flags before boarding the American Banker to visit the graves of their sons killed in France.

Dick Lewis/NY Daily News Archive, Getty Images