Stories of War

Civil War

1861–1865

In 1861, Black people felt the Civil War was a fight for the end of slavery. Yet they could not enlist. “This is no time to fight only with your white hands and allow your black hands to be tied,” Frederick Douglass asserted.

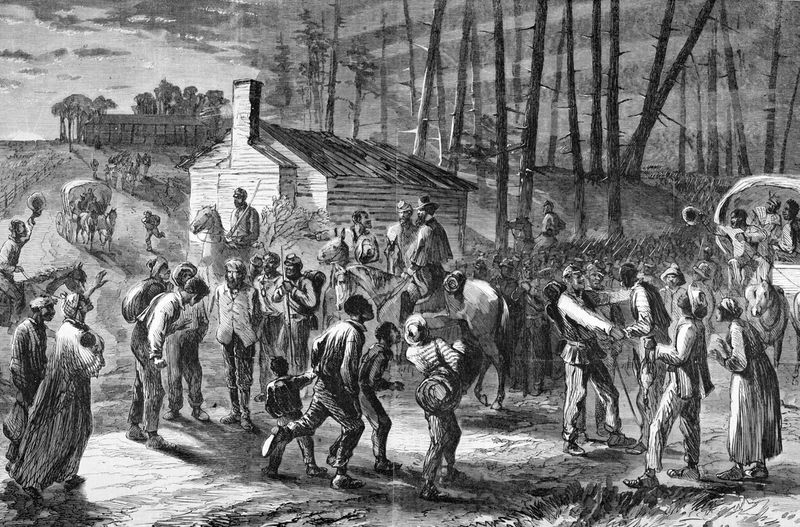

Though barred from service, Black people supported the Union war effort in other ways. Enslaved people flocked to Union lines for protection, and worked as teamsters, cooks, laundresses, and laborers. Lucy Higgs Nichols and her daughter, Mona, arrived in the Tennessee camp of the 23rd Indiana Infantry Regiment in 1862. For the rest of the war, Lucy worked with the soldiers as a nurse, seamstress, and cook.

Colored Troops under General Wild, liberating enslaved people in North Carolina.

Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora

President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, which took effect January 1, 1863, opened the door to enlistment. But some didn’t wait for permission. Harriet Tubman went to South Carolina in 1862 ready to fight. In June 1863, she became the first woman to help lead an armed assault by U.S. troops when she guided three Union gunboats on a raid up the Combahee River. The mission liberated around 750 enslaved people. Robert Smalls also made headlines for irregular service when he piloted a ship loaded with Confederate guns and ammunition past several South Carolina forts and into Union lines.

A young Harriet Tubman.

National Museum of African American History and Culture

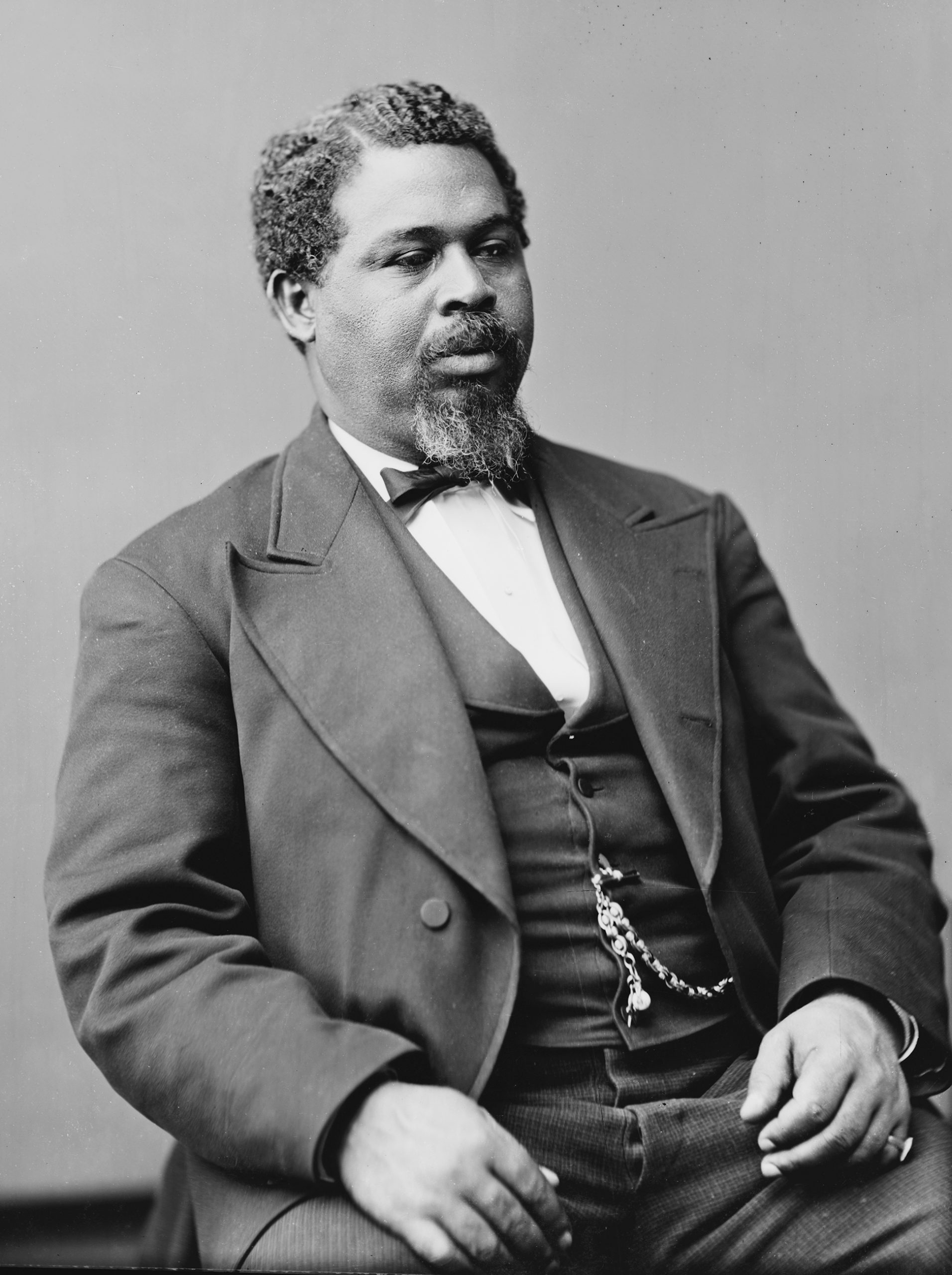

After escaping the Confederacy aboard a stolen ship, Robert Smalls went on to be elected to Congress. Featured is his U.S. House of Representatives portrait.

Library of Congress

In May 1863, the War Department authorized regiments of U.S. Colored Troops (USCT), recruited from all states. When the governor of Massachusetts announced a regular army regiment of Black volunteers, so many people flocked to enlist that two regiments were formed: 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, and the 55th.

The 54th Massachusetts and other USCT units famously led an assault on Fort Wagner, near Charleston, in July 1863. These brave men were assigned the lead position for a frontal assault on walls up to thirty feet high and reached the parapet in two places. The charge failed to take the fort, but it was indisputable proof of Black Americans’ courage and valor.

A recruitment poster for the United States Colored Troops, used to encourage others to join the fight in liberating those who remained enslaved.

National Museum of American History

Union soldiers close in on the walls of Fort Wagner on Morris Island, South Carolina and engage Confederate soldiers in hand-to-hand combat.

Library of Congress

Sergeant William H. Carney was the first Black recipient of the Medal of Honor: “When the color sergeant was shot down, this solder grasped the flag, led the way to the parapet, and planted the colors thereon. When the troops fell back, he brought off the flag, under fierce fire in which he was twice severely wounded.”

His courage is even more remarkable knowing that Black servicemen were offered lower pay than their white counterparts. Hiram Peterson, Sgt. Co. G, 2nd Regiment, USCT New York, wrote to his father to tell him he received only seven dollars that month, when he was owed seventeen. Peterson’s father wrote to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. The 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry refused to accept pay for 18 months when offered seven dollars a month instead of the thirteen offered to white private soldiers. In September 1864, Congress equalized the pay rates. The back pay, said Sergeant Francis Fletcher, did not make up for the suffering the men’s families at home endured.

Sergeant William H. Carney, the 1st African American awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for valor during the Civil War.

National Museum of African American History and Culture

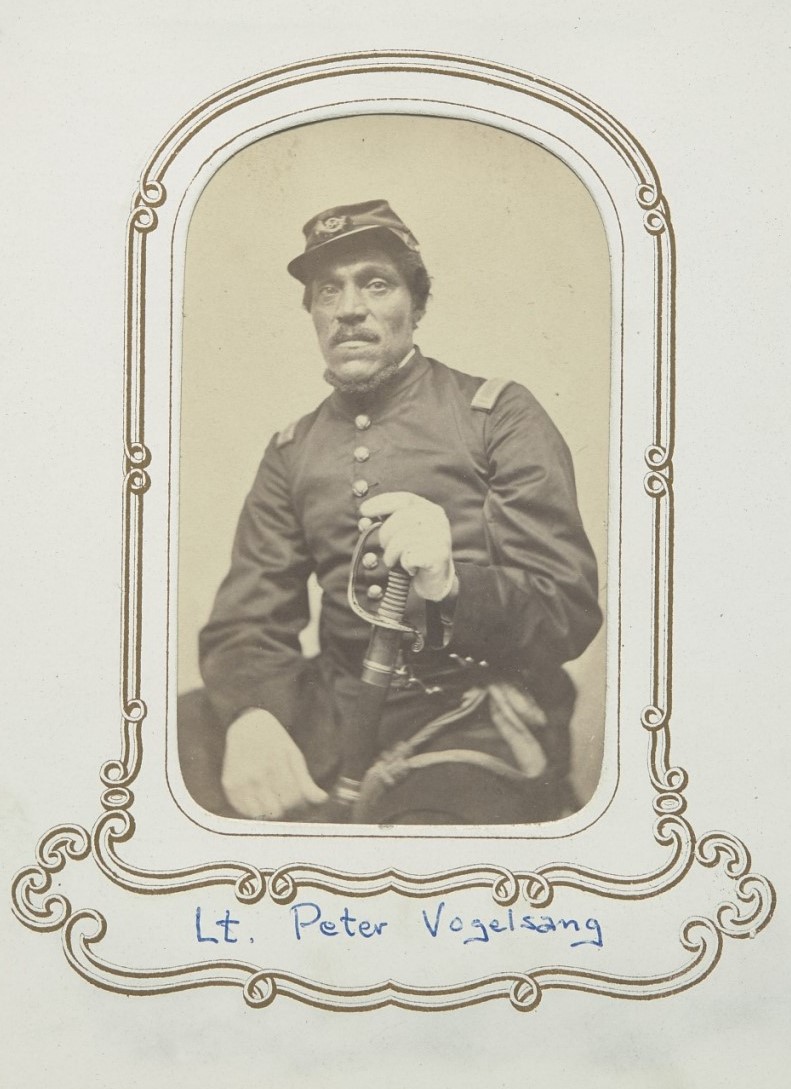

Lieutenant Peter Vogelsang, who served with the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment.

National Museum of African American History and Culture

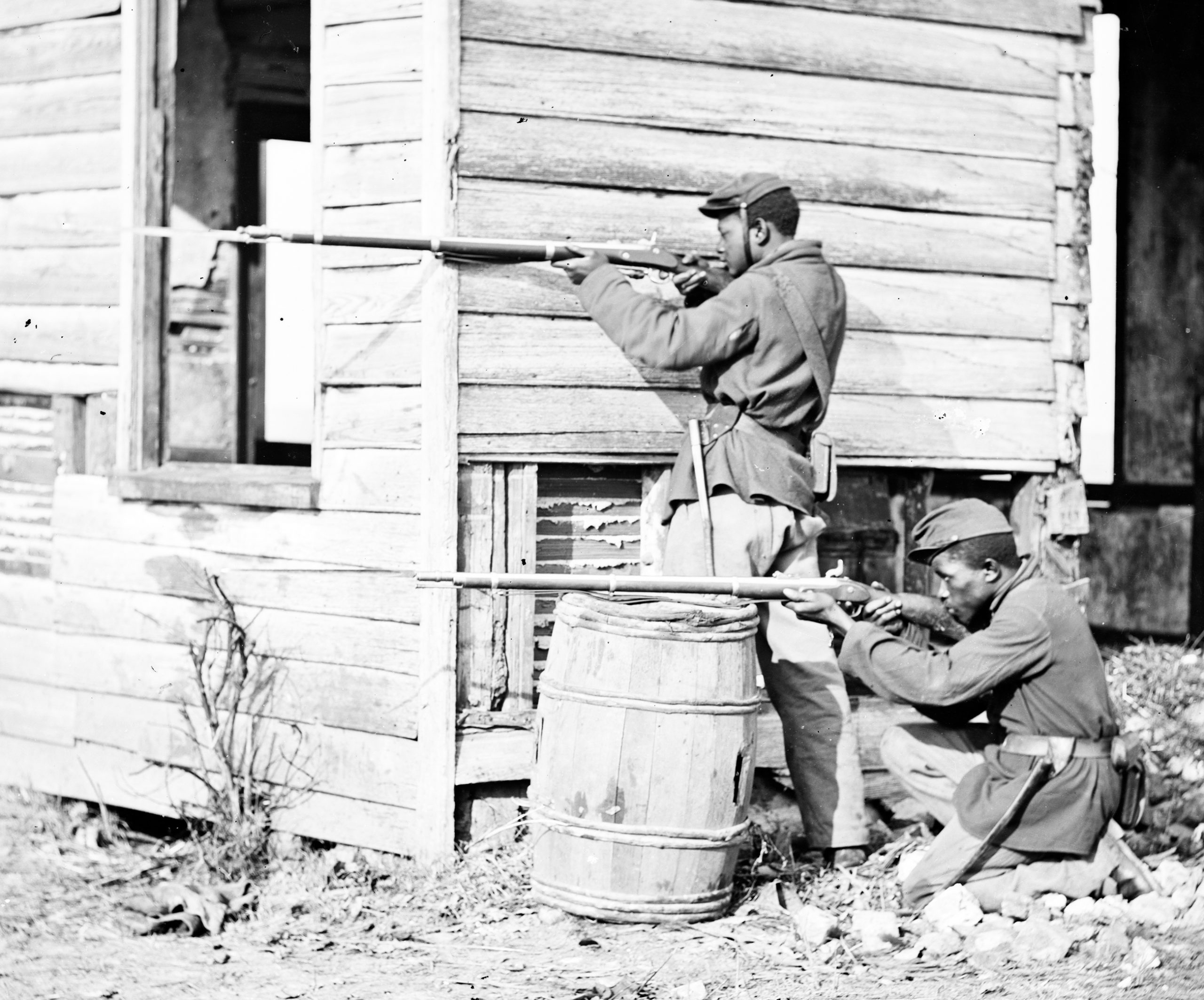

Two newly enlisted Union soldiers pose with their Springfield Armory Model 1861 rifle-muskets.

Library of Congress