Stories of War

American Indian Wars

1817–1890

In 1866, Congress established six all-Black regiments for peacetime work. Black soldiers who stayed in the military after the U.S. Civil War served in the 9th and 10th Cavalry regiments, and in the 38th, 39th, 40th and 41st Colored Infantry Regiments. In 1869, these four units were reorganized into the 24th and 25th Infantry regiments.

These brave Black troops served during an unprecedented period of U.S. expansion across North America. Native Americans recognized that Black troops were different. Some called them “Buffalo Soldiers,” referring to the appearance of their curly hair and courage in battle. For a time, that name became synonymous with all Black soldiers. Today, it refers only to the U.S. Army units that trace their lineage back to any of the original all-Black units formed in 1866.

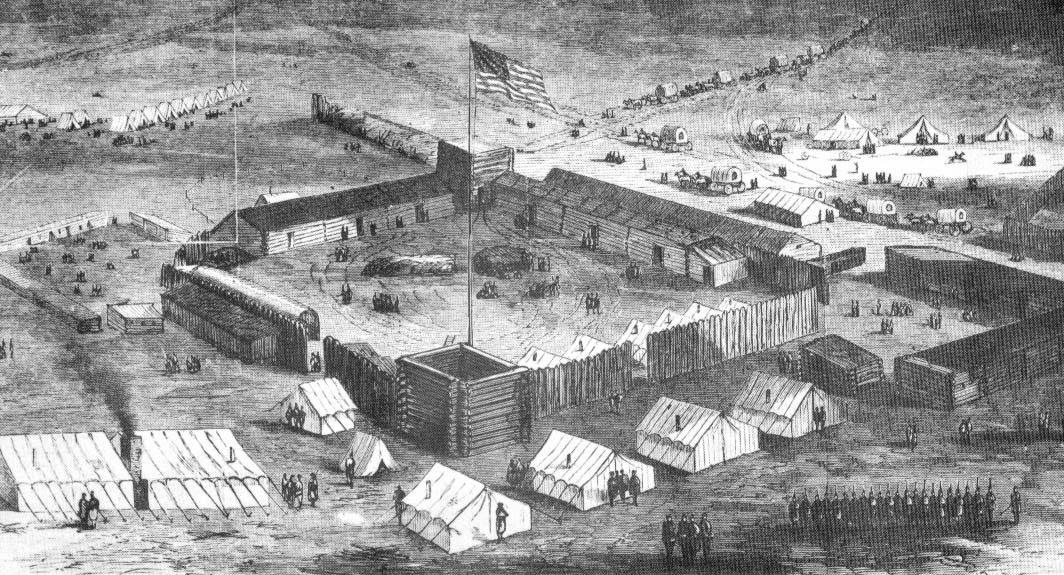

Military stockade near Beaver River and Wolf Creek (north fork of Canadian River), Utah.

Library of Congress

For their part in the decades-long Indian wars, 18 Buffalo Soldiers were awarded the Medal of Honor, including John Denny. Denny, who served for 30 years in the 10th and then the 9th Cavalry, earned the honor in 1879 in New Mexico when he ran through heavy fire to bring a wounded comrade to safety.

The Buffalo Soldiers’ service involved much more than fighting. They built roads, laid telephone and telegraph wire, surveyed land, guarded railroads, kept the peace, assisted with U.S. Mail service, and staffed forts.

One Buffalo Soldier, William Cathey, enlisted in 1866 in St. Louis, Missouri for a three-year term in the 38th Infantry. While there is no record of combat, the soldier’s life was difficult. Cathey and his comrades were exposed to extreme weather, living in tents or rough shelters. They marched great distances on meager and monotonous rations and dealt with shortages and low-quality equipment. Cathey’s service ended in 1868, when he was discharged in New Mexico due to “feeble” health.

The most remarkable part of Cathey’s service was not the hardships, but that he was a woman: Cathay Williams. During the Civil War, Williams had worked as a cook traveling with General Philip Sheridan’s army. Her years of living among soldiers enabled her to “blend in” even in close quarters.

She was not the only servicewoman to disguise herself as a man; several hundred women are recorded as serving during the Civil War, even in combat. But Williams is the first black woman with documentation of her service in the U.S. armed forces. While there is no first-person testimony of Williams’s experiences or why she enlisted, the service she gave her country—like that of all the Buffalo Soldiers—was undeniable.